| Login | ||

Healthcare Training Institute - Quality Education since 1979

CE for Psychologist, Social Worker, Counselor, & MFT!!

Section 25

Loss & Bereavement and How the Creative Arts Can Help

Part I

Question 25 | Test | Table of Contents

This article looks at how a child who is experiencing loss or bereavement can become stuck in the grieving process and how this can have an adverse effect on the child’s capacity to learn and behave appropriately. The aim of the article is to show how we, as caring adults, can guide a child through the process of grieving, so that eventually the death or loss is accepted and the pain and sorrow lessened, thus preparing the child to reinvest in his or her life. This process of helping is enabled through working with the creative arts and to illustrate this I have selected the case studies of two adolescent boys. I would like first of all to set the scene by taking a closer look at what is meant by loss and bereavement and the possible implications this might have for teachers.

Types of Loss

Losses are of course common in all our lives. And in so far as grief is the reaction to loss, grief must surely be common too. Grief is usually reserved for the loss of a loved person but it can also be the reaction to the loss of a pet, moving house or changing schools; it can also be brought on through loss of a belief or self-esteem. Every kind of personal growth and change may be cause for grief. These are what Elizabeth Kubler-Ross (1969) calls the ‘little deaths’ of life. It may be argued that if we would face everyday changes and practice letting go in our daily lives, perhaps loss and grief would be less traumatic. However, the effect of the death or loss of one we love can be so great that our personal experiences with ‘little deaths’ may never adequately prepare us. At other times it may be the multitude of ‘little deaths’ that can overburden the grieving process.

What is Grief?

When a love tie is severed, a reaction, emotional and behavioral, is set in train which we call grief (Parkes, 1991, p. 1).

Grief is the reaction to loss. It can be intense and multifaceted, affecting our emotions, our bodies and our lives. According to Tatelbaum (1995) it is preoccupying and depleting. Emotionally, grief is a mixture of raw feelings, such as sorrow, anguish, anger, regret, longing, fear, and deprivation. Grief may be experienced physically as exhaustion, emptiness, tension, sleeplessness, or loss of appetite. On the whole, grief resembles a physical injury more closely than any other type of illness. The loss may, as Parkes (1991) writes, be spoken of as a ‘blow’. As in the case of a physical injury, the ‘wound’ gradually heals but sometimes there may be complications, thus delaying the healing process or a further ‘injury’ re-opens the existing wound. Grief is a process and not a state: it is not a disease. Many of the grieving processes have been based on the observation of patterns and similarities. Probably the best known of these models is the stage-centered model of Kubler-Ross (1982) which sees the individual moving from shock and denial to searching, then anger followed by depression and guilt before reaching a stage of resolution. Emergence from grief can be described in terms of living again, rather than simply existing. Knowledge of the stages of grief can help teachers to understand and prepare for grief in bereaved children (Holland and Ludford, 1995).

Children and Grief

Children need to be able to work through their grief but, unfortunately, they all too often hold back their questions and tears for fear of upsetting the adults close to them. By inhibiting their own grief, they are probably going to function below their potential, as initially they may be preoccupied with shock and later with depression. Evidence of depression as well as school refusal was highlighted by Black (1974) whilst Brown et al. (1977) and Hill (1967) found connections between adult depressive illness and childhood bereavement.

Blackburn (1991) identified a mismatch between the needs of grieving children and the perceptions of their teachers. His research gave a clear indication that bereavement can disrupt the education process at both primary and secondary levels. Postal research carried out by Holland and Ludford (1995) adds weight to previous findings. They found that 87% of schools which replied, reported post-bereavement psychological or physical problems: anger and depression; withdrawal symptoms; distress; and attention seeking behaviors. Staff also noticed a lack of motivation and increased absenteeism. It is without doubt that children do experience loss, which can hurt them as much as it does adults. They too need to be able to express their loss in a safe environment. They need to be able to share their fears, doubts, and questions. Unable to do so or denied access to this process, a destructive pattern of swallowing feelings may follow. Loss and bereavement can be particularly threatening for adolescents, who may develop fears of separation and independence. Because teenagers often appear more mature, better able to mask their feelings than children, their grief feelings can become unhealthily buried.

Reacting to Death and Loss

Teachers and non-teaching staff alike can help by reacting with warmth and caring, by conveying the message, ‘I am trying to understand how you are feeling and I want to help if you will let me’. If a child wants to talk then there is no better way of helping than by finding the time to listen. By listening in a caring, supportive and reassuring way the child will soon realize that the listener does care and is there to help. By also allowing the child to feel and express emotion, staff are giving reassurance that grief is not shameful.

When the Grieving Process Gets Stuck

Even the strongest of support structures, home or school, might find itself unable to rescue one or more of its children. When a child becomes stuck in the grieving process, a more specialist form of help might be needed. There is a growing awareness of the need for specialist help, shown in the development of individual and group support programs available in and out of the school environment. For the purpose of this work I would like to focus on one to one helping sessions using the creative arts.

How Creative Art Therapy can Help

Therapeutic use of the Arts can help us to work from the inside out. By acknowledging and experiencing our feelings we can release them. If a part of us continually harbours the feelings we ignore, we are left only with a part of ourselves for the process of living (Oaklander, 1988). Working with the Arts can feel safe for the child. It can create a safe place for an emotional discharge, at other times pictures or play may enable the expression of the struggle and confusion surrounding a loss or multiple losses which the child may only be able to express non-verbally. It can also be a way of working through unacceptable feelings. The process, as pointed out by Oaklander (1988) is not a means to an end. It is actually the process that is important; the ‘acting out’.

Thomas

Thomas was tall for his 12 years. He was of smart appearance, polite, friendly, and well spoken. He was first referred to me just over a year ago, as a result of his unacceptable behavior in class. The standard of work produced was generally good, but with room for improvement. Teachers were concerned about the low level disruptive behaviors he was displaying during their lessons. When teachers were asked to identify specific behaviors, they made reference to calling out, silly faces, silly voices and noises, sulky manner, and answering back. There was no other background information, other than the knowledge that his father had died unexpectedly some 14 months before. To the best of his mother’s knowledge, Thomas had spoken to no one about his father’s death and had certainly never shared his pain with her. She was finding him increasingly difficult at home and was becoming upset over his laziness and insolence.

At this stage, I suspected that Thomas had become ‘stuck’ in the grieving process. His father’s death might perhaps be described as an unresolved issue from the past, therefore affecting the present and interactions in the present. Unfinished business stops us from completing the gestalt cycle or gaining a or resolution. I suspected that Thomas was seeking completion in compulsive and repetitive inappropriate behavior; for Thomas, perhaps a means to survival.

Thomas seemed genuinely surprised that my intervention had been called for. His perception was that he did call out sometimes and perhaps occasionally answered back, but then, so did quite a few others. As for silly noises or faces, he denied this categorically he would not be that immature! Thomas enjoyed talking about his interests and hobbies, his likes and dislikes and his past, present and future. His interests included basketball and drawing. I felt that I had gained his trust; I had given Thomas genuineness, warmth, empathy and unconditional positive regard —essential to the counseling relationship. Yet I felt that Thomas was harboring the feelings surrounding the loss of his father. It was as though through telling stories, he was denying the true sensation of his sadness. I believed that the use of creative arts might enable exploration of such feelings. With this in mind, I asked Thomas if he would like to draw next time. Yes, he would like that.

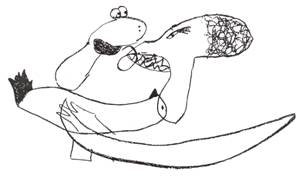

I chose to use the continuous line or ‘scribble’ technique which is simply a freely flowing line drawn on paper using the non-dominant hand whilst the eyes are closed, for approximately 30 seconds. The line may intertwine or be clear and simple. Through using this technique it is hoped that images are released from the unconscious.

When Thomas completed his line (Figure 1) I asked him to identify two animal or human shapes within the boundary of that line. He quickly identified two ‘alien’ shapes which were moving very fast through outer space. The one on the right, colored purple and red, was being obstructed by the green and red alien on the left. When I asked where the alien on the right was going, Thomas replied, ‘Nowhere in particular’.

When Thomas completed his line (Figure 1) I asked him to identify two animal or human shapes within the boundary of that line. He quickly identified two ‘alien’ shapes which were moving very fast through outer space. The one on the right, colored purple and red, was being obstructed by the green and red alien on the left. When I asked where the alien on the right was going, Thomas replied, ‘Nowhere in particular’.

However, because this alien was more aggressive and bigger than the other one, he succeeded in getting away. Since hurt feelings are so commonly buried under a layer of angry feelings, Oaklander (1988) says that it is very threatening and difficult for children to get through the angry surface feelings to allow full expression of the authentic sub-surface feelings. Through drawing, and verbalizing what he saw, Thomas was able to find ‘acceptable’ ways of dealing with feelings of anger whilst paving the way for all the pain he had so far denied. When asked to find a third shape of any sort, Thomas outlined a boat, followed almost immediately by a penguin, drawn very faintly. The boat was to enable the penguin to drift out to sea. Was the boat offering Thomas security; a container to further protect him from the sensation of pain?

A penguin was to appear in subsequent work. During the next session a penguin was drawn looking out to sea (Fig. 2). At the end of this session, I mounted both drawings on the wall and asked Thomas, ‘What do you see?’ After a minute or two of quiet reflection the following dialogue took place.

A penguin was to appear in subsequent work. During the next session a penguin was drawn looking out to sea (Fig. 2). At the end of this session, I mounted both drawings on the wall and asked Thomas, ‘What do you see?’ After a minute or two of quiet reflection the following dialogue took place.

Thomas: I see two aliens in conflict. One looks sulky. I suppose you think that’s really me, don’t you?

Me: Do you feel that he is like you? [a pause]

Thomas: I suppose he is, a bit. I can be a bit sulky and grumpy sometimes.

Me: So you feel you can be sulky and grumpy like your alien. What else do you see?

Thomas: I see a cat, two penguins and a boat. [Further pause for reflection]

Me: What are you feeling right now?

Thomas: Everything is sort of drifting around and searching for something. That’s it! They are all looking for something!

Me: So you feel they are all looking for something. What is that something, do you think?

Thomas: I don’t know.

The following week, Thomas chose to work with clay. Having spent around 20 minutes pummeling and tearing his clay, all the while frowning and appearing very intent on the task, he eventually modeled his clay into the likeness of a person he disliked. When asked what he would like to do with this creation, he said he would like to destroy it, and proceeded to do so, limb by limb! This had enabled him to express anger in a safe way. He then went on to model a penguin, which he took home.

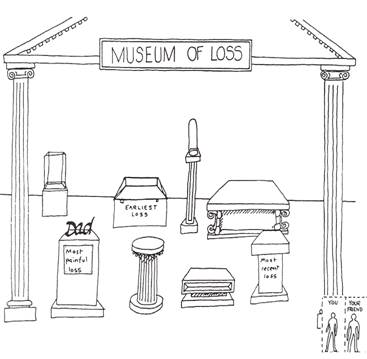

Following on from his theme of searching, from the previous weeks, I introduced Thomas to Margot Sunderland’s ‘Museum of Loss’. The object of this exercise was to enable Thomas to explore feelings of loss, and therefore gain relief through talking about and sharing such feelings. I told Thomas that when he had completed the task, he may speak in as much or as little detail as he feels comfortable with. Thomas sat for a long time looking at the paper in front of him. Above the ‘Most Painful Loss’ stand (Figure 3) he simply wrote, ‘Dad’. He left the rest blank and put his pen down. His eyes filled and no amount of brushing aside could stop the tears from flowing. I said it was OK to cry and that it seems that he has been carrying around a lot of sadness and pain. Through his tears he told me that this was the first time he had cried since his dad had died. Using the empty chair scenario, Thomas went on to tell his dad how much he loved and missed him. He said he wished he was with him still, and told him how well he was doing at basketball. He said he wanted him to be proud of him.

Following on from his theme of searching, from the previous weeks, I introduced Thomas to Margot Sunderland’s ‘Museum of Loss’. The object of this exercise was to enable Thomas to explore feelings of loss, and therefore gain relief through talking about and sharing such feelings. I told Thomas that when he had completed the task, he may speak in as much or as little detail as he feels comfortable with. Thomas sat for a long time looking at the paper in front of him. Above the ‘Most Painful Loss’ stand (Figure 3) he simply wrote, ‘Dad’. He left the rest blank and put his pen down. His eyes filled and no amount of brushing aside could stop the tears from flowing. I said it was OK to cry and that it seems that he has been carrying around a lot of sadness and pain. Through his tears he told me that this was the first time he had cried since his dad had died. Using the empty chair scenario, Thomas went on to tell his dad how much he loved and missed him. He said he wished he was with him still, and told him how well he was doing at basketball. He said he wanted him to be proud of him.

Thomas had become stuck in the grieving process and in denying his loss he was hurting not only himself but other significant people in his life. As our sessions progressed, Thomas had gradually explored his feelings. Acceptance of his father’s death and emergence of all the painful feelings surrounding this incredibly painful loss, enabled Thomas to ‘let go’ and begin picking up the threads of a new identity.

- Count, D. L. (2000). Working with Difficult Children from the Inside Out: Loss and Bereavement and How the Creative Arts Can Help. Pastoral Care in Education, 18(2), 17-27. doi:10.1111/1468-0122.00157

Update

How the Arts Help Us Hold Grief

and Maintain Collective Care

- Rynders T. (2022). How the Arts Help Us Hold Grief and Maintain Collective Care. AMA journal of ethics, 24(7), E681–E684.

Peer-Reviewed Journal Article References:Donohue, M. R., & Tully, E. C. (2019). Reparative prosocial behaviors alleviate children’s guilt. Developmental Psychology, 55(10), 2102–2113.

Kiser, L. J., Miller, A. B., Mooney, M. A., Vivrette, R., & Davis, S. R. (2020). Integrating parents with trauma histories into child trauma treatment: Establishing core components. Practice Innovations, 5(1), 65–80.

Marshall, A. D., Roettger, M. E., Mattern, A. C., Feinberg, M. E., & Jones, D. E. (2018). Trauma exposure and aggression toward partners and children: Contextual influences of fear and anger. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(6), 710–721.

Salinas, C. L. (2021). Playing to heal: The impact of bereavement camp for children with grief. International Journal of Play Therapy, 30(1), 40–49.

QUESTION

25

What is the continuous line or "scribble" technique and its purpose with bereaved children? To select and enter your answer go to Test.